Historical Context of Slavery in Martinique

The history of slavery in Martinique is deeply intertwined with the island’s plantation economy, which flourished primarily from the 17th century onward. As a French colony, Martinique became a crucial player in the production of sugar, a lucrative commodity that relied heavily on the labor of enslaved Africans. The demand for sugar in Europe was insatiable, leading to a significant increase in the importation of enslaved individuals from Africa. By the 18th century, a large majority of the island’s population consisted of enslaved persons, creating a society where the economy was heavily dependent on forced labor.

The transatlantic slave trade saw millions of Africans transported under dire conditions to the Americas, including Martinique, where they were subjected to brutal working conditions on sugar plantations. This inhumane system not only dehumanized the enslaved individuals but also shaped the social fabric of the colonial society, fostering disparities between the wealthy plantation owners and the oppressed enslaved population. The cultural impact of slavery was profound, as African traditions, languages, and spiritual practices mingled with European influences, creating a unique Creole identity that remains in parts of Martinique today.

<pthroughout 1848="" 19th="" a="" abolition="" abolitionist="" along="" and="" as="" awareness="" began="" both="" brutal="" by="" calls="" caribbean="" century,="" challenge="" combined="" conditions="" coupled="" due="" enlightenment="" enslaved="" equality,="" ethical="" faced="" factors="" for="" gained="" haitian="" history.

The Abolition Movement and Key Figures

The abolition movement in France and the Caribbean is a complex tapestry woven from the courage and determination of numerous individuals across different spheres of society. The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed a growing awareness of the inhumanity of slavery, significantly influenced by the principles of liberty and equality propagated during the French Revolution. The ideals of 1789 ignited a sense of urgency among abolitionists, who recognized that the time for change had come. In the Caribbean, including Martinique, a confluence of economic, social, and political factors set the stage for significant developments.

Among the pivotal figures in the abolition movement, Victor Schœlcher stands out as a tireless advocate for the emancipation of enslaved individuals in the French colonies. Appointed as a commissioner to investigate the conditions of slaves in the colonies, Schœlcher fervently campaigned for abolition, arguing that the so-called “civilized” nations had a moral obligation to end slavery. His relentless efforts culminated in his role in drafting the decree that officially abolished slavery in Martinique on April 27, 1848. Additionally, the voices of formerly enslaved individuals were critical in advocating for change, as they shared their harrowing experiences and called for an end to their subjugation.

The influence of international movements also played a crucial role in the local abolitionist efforts. In the context of the wider Caribbean, abolitionist sentiments were buoyed by the successes of emancipation in other territories, as they bolstered the aspirations of those in the colonies. Political leaders and activists collaborated to cultivate a burgeoning civil rights consciousness among the populace, resisting the entrenched interests of plantation owners who sought to maintain their economic power through slavery. This collective mobilization ultimately resulted in a significant shift in public opinion and paved the way for the long-awaited end of slavery in Martinique.

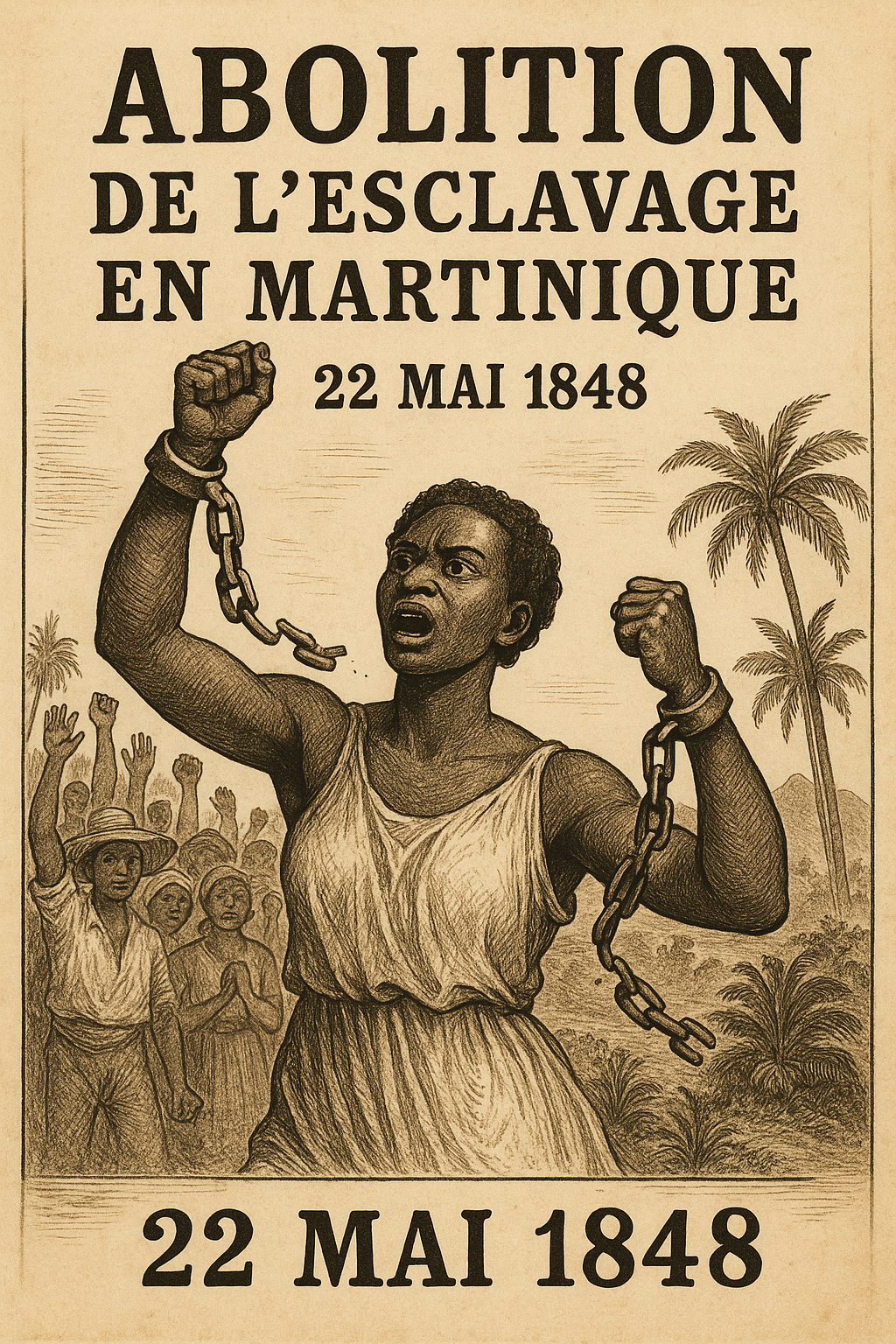

The Decree of Abolition in 1848

In April 1848, the French government issued a decree that fundamentally altered the socio-political landscape of Martinique by abolishing slavery. This decree came at a time when France was undergoing significant political transformations, particularly following the February Revolution of 1848, which resulted in the establishment of the Second Republic. As a part of this reform movement, the National Assembly was influenced by growing humanitarian sentiments and the evolving discourse surrounding human rights, leading to the realization that slavery was incompatible with the ideals of liberty and equality that the revolution professed.

The implications of the decree for the enslaved people in Martinique were profound. It legally transformed their status from property to individuals endowed with certain rights, fundamentally altering the power dynamics between the formerly enslaved and their masters. However, the immediate response from plantation owners and the colonial administration was one of apprehension and resistance. Many landowners expressed their discontent, fearing economic collapse and loss of labor. In the wake of abolition, they sought ways to undermine the decree, while the colonial administration scrambled to manage the transition, often failing to provide adequate support and resources for the newly freed individuals.

The local population received the news of abolition with a mix of jubilation and skepticism. Enslaved people celebrated their newfound freedom, organizing gatherings and public displays of gratitude. However, the implementation of the decree faced numerous challenges, including a lack of clear guidelines on how to transition from a slave-based economy to one founded on wage labor. Despite these obstacles, the decree of abolition marked a momentous shift in Martinique’s history, setting in motion a complex interplay of social, economic, and political changes that would redefine the island’s future for generations to come.

The Aftermath and Legacy of Abolition

The abolition of slavery in Martinique in 1848 marked a significant turning point in the island’s history, with profound implications that shaped its social, economic, and political landscape. Following the proclamation of freedom, a complex transition was initiated, wherein formerly enslaved individuals began to navigate their new status as free citizens. This transition, however, was fraught with challenges, as many freed people struggled with the abrupt shift from a lifetime of enforced labor to self-sustenance and economic independence.

Socially, the sudden end of slavery altered the fabric of Martinican society. The formerly enslaved population sought to reclaim their identity and cultural heritage, which had been suppressed during slavery. This reawakening fostered a sense of community and solidarity among the liberated individuals, leading to the formation of new social structures that prioritized education, cultural expression, and economic collaboration. However, the legacy of enslavement continued to weigh heavily on these communities, as systemic inequalities persisted, manifesting in limited access to resources, political representation, and social services.

Economically, Martinique faced transformation challenges, as the plantation economy heavily relied on enslaved labor. The transition to wage labor required significant adaptations in agricultural practices and labor relations. Many plantations shifted to a system that employed former slaves under precarious conditions, often leading to dissatisfaction and unrest. Despite these hardships, the abolition of slavery laid the groundwork for future economic reforms and labor rights advocacy, influencing generations of labor movements on the island.

Politically, the abolition of slavery instigated discussions around citizenship, rights, and identity in post-colonial contexts. The legacy of the abolition movement reverberates through contemporary dialogues about race, heritage, and justice in Martinique. As society grapples with the historical injustices and their modern-day implications, the struggle for recognition and healing remains central to the island’s identity.

One Response

I believe this web site contains some real excellent information for everyone : D.