Benjamin Banneker: The Man Who Measured the Stars and Helped Build America

Benjamin Banneker was born in 1731 in rural Maryland, at a time when knowledge was tightly controlled and opportunity was rationed by class, race, and access. He was born free, yet freedom in colonial America did not include schools, institutions, or formal pathways into science or public life. What Banneker possessed instead was an uncommon discipline of mind, a relentless curiosity, and the ability to teach himself in a world designed to exclude him. From an early age, Banneker demonstrated a deep attentiveness to patterns. He observed the movement of shadows, the rhythm of seasons, the cycles of the moon, and the quiet logic underlying numbers. These observations were not passive. They became the foundation of a rigorous self-education in mathematics, astronomy, mechanics, and natural philosophy. Without classrooms or instructors, he relied on borrowed books, correspondence, and repeated experimentation. Knowledge, for Banneker, was not inherited or granted — it was earned through persistence. One of his earliest achievements revealed the breadth of his mechanical intelligence. After examining a pocket watch, Banneker constructed a fully functional wooden clock entirely by hand. At a time when precision timekeeping was rare and highly specialized, his clock reportedly kept accurate time for decades. This was not novelty craftsmanship. It was applied engineering — a synthesis of measurement, geometry, and mechanical reasoning executed with remarkable precision. Banneker’s attention soon turned upward to the night sky. Astronomy in the eighteenth century demanded advanced mathematical ability, extended observation, and exact calculations. Without formal training, Banneker mastered celestial mechanics well enough to calculate planetary positions, track lunar cycles, and accurately predict eclipses. These were not theoretical exercises. They became published data used by others. Between 1791 and 1796, Banneker authored and published a series of almanacs containing astronomical calculations, weather forecasts, tide tables, and practical information essential for farmers, navigators, and merchants. Almanacs were critical tools in early American life, shaping agricultural planning and commerce. Banneker’s editions were valued for their accuracy and circulated widely throughout the Mid-Atlantic region. His work entered daily life quietly, efficiently, and without spectacle. It was this reputation for precision that brought Banneker into one of the most consequential projects of the young nation: the surveying of the federal district that would become Washington, D.C. In 1791, he was appointed as an assistant to the survey team responsible for mapping the boundaries of the future capital. Using astronomical observations and mathematical calculations, Banneker helped establish the layout of the city. According to historical accounts, when the original design plans were lost following the departure of the chief planner, Banneker reproduced the layout from memory — an extraordinary demonstration of spatial reasoning and intellectual command. At the same time, Banneker understood that knowledge carried moral responsibility. In 1791, he wrote a carefully reasoned letter to Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State, addressing the contradiction between Jefferson’s stated belief in liberty and his participation in slavery. Banneker did not rely on rhetoric alone. He appealed to logic, evidence, and shared Enlightenment principles. Enclosed with the letter was a copy of his almanac — not as a plea for validation, but as proof of intellectual equality grounded in demonstrable work. Jefferson responded respectfully and forwarded Banneker’s almanac to intellectual circles in Europe. Yet the system itself remained intact. Still, the exchange endures as one of the most direct intellectual challenges to slavery issued during the early republic — a reminder that resistance did not always take the form of protest, but often appeared as clarity, data, and moral precision. Banneker lived the remainder of his life quietly. He never married, never accumulated wealth, and never sought public acclaim. In 1806, after his death, much of his work was lost in a fire that consumed his home. What survived did so unevenly — scattered across letters, publications, and partial historical records. Over time, his role in the nation’s formation was minimized, simplified, or omitted altogether. Yet Benjamin Banneker cannot be reduced to a symbol or an exception. He was a builder of systems, a producer of usable knowledge, and a contributor to the physical and intellectual infrastructure of the United States. His life stands as evidence that disciplined thought does not require permission, and that nation-building has always depended on minds history later chose not to emphasize. To study Benjamin Banneker is to confront a deeper truth about America’s origins: that progress was shaped not only by those whose names dominate monuments, but by thinkers whose work spoke for itself long before recognition followed. His legacy is not confined to clocks, almanacs, or survey lines. It is the enduring reminder that knowledge, once proven, cannot be erased — only delayed. Focus Keyphrase:Benjamin Banneker Washington DC Slug:benjamin-banneker-washington-dc Meta Description:Discover the true story of Benjamin Banneker, the self-taught polymath whose astronomical calculations and surveying work helped shape Washington, D.C., and challenged the contradictions of America’s founding ideals.

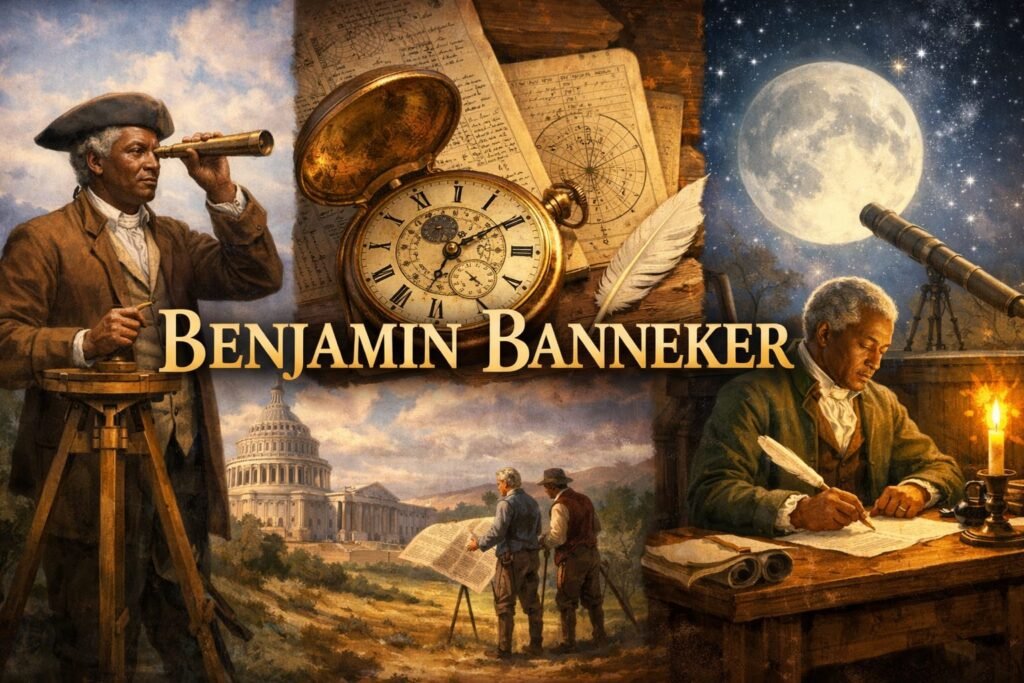

Frederick McKinley Jones: The Black Inventor Who Revolutionized Refrigeration and Global Food Supply

Before refrigerated trucks, the world ate locally, lived seasonally, and lost enormous amounts of food to spoilage. Fresh meat rarely traveled far. Produce rotted before reaching cities. Vaccines and blood plasma often expired before arriving where they were needed most. Entire regions were constrained not by demand, but by distance. Modern life as we know it simply wasn’t possible yet. That reality changed because of Frederick McKinley Jones. Born in 1893, Jones did not grow up with access to elite schools, laboratories, or wealthy patrons. He was largely self-taught, learning mechanics, engineering, and electronics through curiosity and necessity rather than formal education. In an America that routinely dismissed Black intelligence, Jones quietly mastered complex systems that others struggled to understand. He fixed machines. He improved them. And eventually, he redesigned an entire industry from the ground up. Jones recognized a problem most people had accepted as unavoidable: perishable goods could not survive long journeys. The solution wasn’t simply ice or insulation. It required a compact, reliable, mobile system capable of maintaining controlled temperatures while in motion. At the time, that idea bordered on impossible. Vehicles vibrated. Engines overheated. Roads were rough. Power sources were inconsistent. Yet Jones engineered a self-contained refrigeration unit strong enough to withstand travel and precise enough to preserve food and medicine. His invention of mobile refrigeration systems transformed transportation forever. Trucks, trains, and ships could now carry fresh goods across long distances without loss. Farms were no longer limited to nearby markets. Cities could grow larger without risking food shortages. Seasonal eating gave way to year-round availability. Grocery stores evolved. Supply chains expanded. Entire industries were born almost overnight. The impact reached far beyond food. During World War II, Jones’s refrigeration technology was used to transport blood plasma and medical supplies to soldiers overseas. Lives were saved not by battlefield heroics, but by temperature control. Quiet engineering became silent survival. Jones went on to earn more than sixty patents across refrigeration, engines, and electronics. He co-founded what would later become Thermo King, a company that still dominates global refrigeration transport today. Billions of dollars move through systems built on his ideas. Every refrigerated truck on the highway traces its lineage back to his work. And yet, for decades, his name was absent from classrooms, textbooks, and mainstream discussions of American innovation. This pattern is not accidental. Black inventors have repeatedly solved foundational problems only to watch their contributions be absorbed, rebranded, and monetized by others. The wealth generated often never returned to the communities that produced the ideas. Recognition arrived late, if at all. Frederick McKinley Jones was eventually awarded the National Medal of Technology, becoming the first Black American to receive the honor. It was deserved, but overdue. By then, the world had already been built on his inventions. At Black Dollar & Culture, these stories matter because they reveal something deeper than history. They show how wealth is created at the systems level. Jones didn’t invent a product. He invented infrastructure. He didn’t chase trends. He solved a permanent problem. That is where real leverage lives. Understanding his legacy is not about admiration alone. It is about strategy. Ownership. Protection. Continuity. When we study figures like Jones, we see a blueprint for how generational wealth is actually built — not through visibility, but through necessity and control of essential systems. Every cold chain, every vaccine shipment, every refrigerated aisle is proof that Black innovation has always powered the modern world, even when the world refused to acknowledge it. The work was never invisible. Only the credit was. ❤️ Support Independent Black Media Black Dollar & Culture is 100% reader-powered — no corporate sponsors, just truth, history, and the pursuit of generational wealth. Every article you read helps keep these stories alive — stories they tried to erase and lessons they never wanted us to learn. Slug: frederick-mckinley-jones-black-inventor-refrigerationMeta Description: Frederick McKinley Jones was a Black inventor whose mobile refrigeration technology transformed food distribution, medicine, and global trade.entor whose mobile refrigeration technology transformed food, medicine, and global trade. Learn the story they don’t teach.Slug: frederick-mckinley-jones-black-inventor-refrigeration

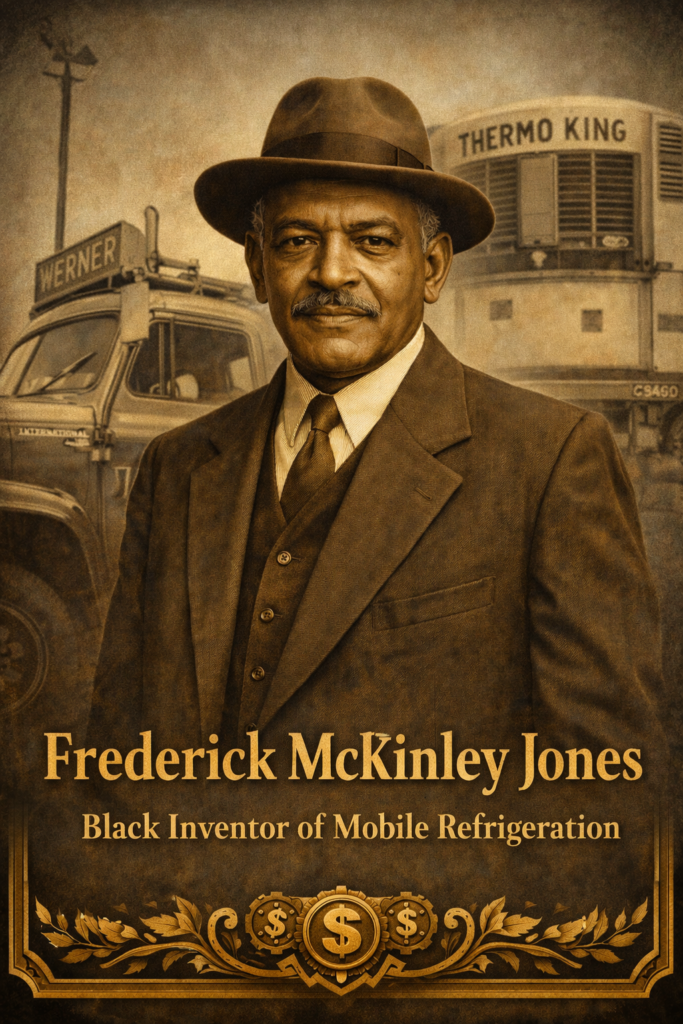

Tuskegee Airmen Black History: The Elite Pilots Who Forced America to End Military Segregation

January 12, 1942 did not arrive with parades, speeches, or national celebration, but history often moves quietly before it roars. On this winter day, in a nation still shackled by segregation and racial mythology, the United States Army Air Forces authorized a program that would challenge one of America’s most deeply held lies: the belief that Black men lacked the intelligence, discipline, and courage to fly military aircraft. From this authorization emerged the men later known as the Tuskegee Airmen—a group whose excellence in the skies would force the nation to confront its contradictions. ❤️ Support Independent Black Media Black Dollar & Culture is 100% reader-powered — no corporate sponsors, just truth, history, and the pursuit of generational wealth. Every article you read helps keep these stories alive — stories they tried to erase and lessons they never wanted us to learn. The establishment of the Tuskegee program did not come from sudden enlightenment. It was the result of pressure, protest, and necessity. Black leaders, civil rights organizations, and newspapers had long challenged the military’s refusal to allow Black pilots, pointing out the hypocrisy of fighting for democracy abroad while denying it at home. World War II, with its demand for manpower, created a crack in the wall. The government conceded, but only partially, and under tightly controlled conditions designed less to empower Black airmen than to test them under a microscope. Training took place at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama, a segregated base in a segregated state. The pilots were trained separately from white counterparts, often with inferior resources, outdated equipment, and instructors who expected failure. Every mistake by a Black cadet was magnified, recorded, and used as supposed proof of racial inferiority. No white unit trained under such pressure. These men were not simply learning to fly; they were fighting an unspoken trial in which the future of Black military aviation hung on every maneuver. Despite these conditions, the men excelled. They mastered navigation, aerial combat, engineering, and leadership. Many already held college degrees at a time when higher education was still largely denied to Black Americans. Their discipline was not accidental—it was forged from the understanding that mediocrity would not be tolerated. Excellence was the minimum requirement for survival, dignity, and progress. When the Tuskegee Airmen were finally deployed overseas, they were assigned to escort Allied bombers deep into enemy territory. This was among the most dangerous missions of the war. Bomber crews depended on fighter escorts to protect them from German aircraft; failure meant death. The Tuskegee Airmen, later known as the “Red Tails” for the distinctive markings on their planes, built a reputation for precision and loyalty. They stayed with the bombers. They did not abandon their posts for personal glory. As a result, they achieved one of the lowest bomber-loss rates of any fighter group in the war. This success directly contradicted decades of pseudoscience and propaganda used to justify segregation. The myth that Black men lacked the mental acuity for complex machinery collapsed under the weight of facts written in combat reports and survival statistics. The myth that Black men lacked courage evaporated in the skies over Europe. What remained was an uncomfortable truth: the barrier had never been ability—it had been racism. Yet recognition did not come easily. While white pilots were celebrated in newsreels and headlines, the Tuskegee Airmen returned home to a country still governed by Jim Crow. They could defeat fascism abroad but not segregation at home. Many were denied jobs in commercial aviation. Some were refused service in restaurants while still wearing their uniforms. The nation had used their skill but hesitated to honor their humanity. Still, history has a long memory, even when institutions try to forget. The success of the Tuskegee Airmen became impossible to ignore. Their record played a crucial role in the 1948 decision by President Harry S. Truman to desegregate the U.S. military, a move that reshaped American armed forces and set a precedent for broader civil rights reforms. Though Truman signed the order, it was the Airmen who earned it with their lives and discipline. The legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen is not confined to military history. It is a lesson in how systems preserve themselves through lies, and how those lies collapse when confronted by undeniable excellence. It is also a reminder that progress in America has rarely been gifted; it has been extracted through pressure, performance, and sacrifice. These men did not simply ask to be included—they proved that exclusion was irrational. Today, when their story is told accurately, it reframes how we understand Black history. It challenges narratives that portray Black advancement as sudden or accidental. The Tuskegee Airmen were scholars, engineers, tacticians, and leaders operating under extreme constraints. Their success was not a fluke; it was the continuation of a long tradition of Black mastery systematically obscured from public memory. January 12 should be remembered not merely as a date, but as a turning point where the lie began to crack. On that day, the United States unknowingly authorized the dismantling of one of its own racist doctrines. The men who trained at Tuskegee did more than learn to fly. They redefined what the nation could no longer deny. They turned the sky into a courtroom, and every successful mission became a verdict. Their story is not just about airplanes or war. It is about truth. And once truth takes flight, it is very hard to bring back down. Focus Keyphrase: Tuskegee Airmen Black HistoryMeta Description: Explore the true story of the Tuskegee Airmen, the Black pilots who shattered racist myths during World War II and reshaped American military history.Slug: tuskegee-airmen-black-history

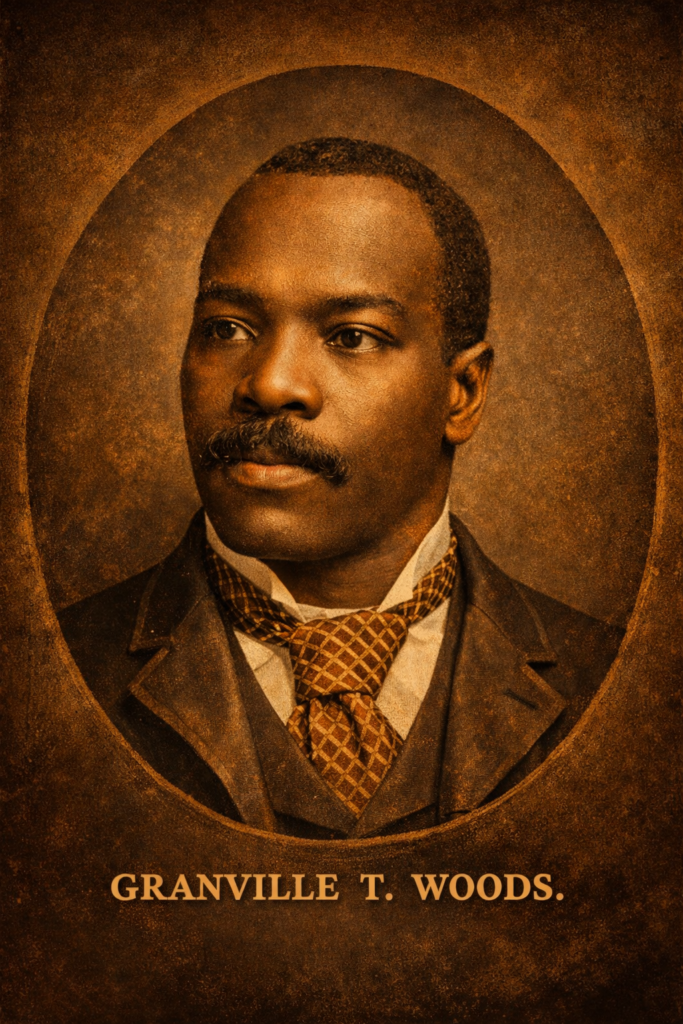

Granville T. Woods: The Black Inventor Who Electrified Modern America

Long before America celebrated innovation as a corporate achievement, before patents became weapons and genius was filtered through race and power, a self-taught Black engineer was quietly reshaping the future of the nation. His name was Granville T. Woods, and the modern world still runs on systems influenced by his mind, even if history has tried to forget him. Born in 1856 in Columbus, Ohio, just one year after the official end of slavery, Woods entered a country that had little interest in protecting Black intellect. Formal education was limited, but necessity became his classroom. As a teenager, he worked in machine shops, steel mills, and on railroads, absorbing mechanical knowledge firsthand. Where others saw labor, Woods saw systems. Where others followed instructions, he asked why things worked—and how they could work better. Railroads in the late 19th century were expanding rapidly, but they were also deadly. Trains collided frequently because communication between moving locomotives and stations was unreliable. Signal systems lagged behind the speed of industrial growth, and passengers paid the price. Woods recognized electricity as the missing link. At a time when electrical engineering was still in its infancy, he envisioned wireless communication between trains and control stations—an idea well ahead of its time. That vision became reality through his invention of the induction telegraph. This system allowed trains to communicate with stations and other trains without physical wires, drastically reducing collisions and improving coordination across rail networks. It was not a minor upgrade; it was a foundational leap in transportation safety. Modern rail signaling, subway communication systems, and even elements of wireless transit technology trace conceptual roots back to Woods’ work. But invention was only half of Woods’ struggle. Ownership was the other. In an America where white inventors were celebrated and Black inventors were questioned, Woods was forced into constant legal battles to defend his patents. Powerful industrial figures challenged his claims, attempting to absorb his ideas into their own portfolios. Among them was Thomas Edison, one of the most famous inventors in American history. Edison disputed several of Woods’ patents, particularly those related to electrical transmission and communication systems. The legal battles were not symbolic—they were brutal, expensive, and exhausting. Yet Woods won. Multiple courts ruled in his favor, affirming that his ideas were original and his claims legitimate. These victories were rare for a Black inventor in that era and underscored the undeniable brilliance of his work. Ironically, after losing to Woods in court, Edison offered him a position at Edison Electric Light Company. Woods declined. He understood that employment would mean surrendering independence and potentially losing control of future inventions. Instead, he chose the harder path: remaining an independent inventor in a system stacked against him. Woods’ contributions extended far beyond railroads. He held more than 60 patents, many focused on electrical systems, power distribution, and transportation. His work improved electric streetcars, helped develop overhead power lines, and advanced the efficiency of electrical transmission in growing cities. Urban America—its subways, trolleys, and commuter systems—benefited enormously from his innovations. Yet unlike his white contemporaries, Woods did not amass wealth. Patent litigation drained his resources. Corporations profited from his ideas while he struggled to maintain financial stability. By the time of his death in 1910, he was respected among engineers but virtually invisible to the public. No fortune. No national recognition. No textbooks honoring his name. This pattern was not accidental. It reflected a broader American reality: Black innovation was essential, but Black ownership was optional. Woods’ story mirrors countless others where genius was extracted, repackaged, and monetized by institutions that refused to credit its true source. His life exposes the uncomfortable truth that America’s technological rise was fueled not just by celebrated inventors, but by marginalized minds denied their rightful place in history. Today, as conversations around equity, ownership, and intellectual property resurface, Granville T. Woods’ story feels painfully modern. He was not merely a victim of his time; he was a warning. Innovation without protection leads to exploitation. Genius without ownership leads to erasure. Restoring Woods to his rightful place is not about nostalgia. It is about understanding the foundation of modern America. The trains that move millions each day, the communication systems that ensure their safety, and the electrical infrastructure that powers cities all carry echoes of his work. His fingerprints are everywhere, even when his name is not. Granville T. Woods was more than an inventor. He was proof that Black intellect has always been central to progress—even when history refused to acknowledge it. Remembering him is not rewriting history. It is finally telling it honestly. Focus Keyphrase: Granville T. Woods Black InventorSlug: granville-t-woods-black-inventorMeta Description: Granville T. Woods was a brilliant Black inventor whose electrical innovations transformed railroads and powered modern America, including winning patent cases against Thomas Edison.

Robert Reed Church: The Black Man Who Became the South’s First Millionaire After Slavery

They don’t teach this story in schools because it disrupts a lie that America has spent centuries protecting—the lie that Black people never built wealth on their own, never mastered systems, never owned power before it was taken from them. Robert Reed Church did all three. Born enslaved in Mississippi in 1839, Robert Reed Church entered the world as property. His mother was enslaved. His father was a white steamboat captain who never publicly claimed him but quietly ensured that Church learned something most enslaved people were denied—how money moved. By the time emancipation arrived, Church was no longer just free. He was prepared. While many newly freed Black Americans were pushed into sharecropping—a system designed to trap them in permanent debt—Church made a different decision. He went where money flowed: the Mississippi River. As a young man, he worked on steamboats, not just as labor but as a businessman. He learned routes. He learned trade. He learned leverage. And most importantly, he learned land. After the Civil War, Memphis was chaos. Disease, political instability, and racial violence made white property owners panic. During the yellow fever epidemics of the 1870s, thousands fled the city. Property values collapsed. White landowners sold prime real estate for pennies just to escape. Robert Reed Church saw opportunity where others saw collapse. With cash saved from years of disciplined work and investing, Church bought land—lots of it. Downtown Memphis. Beale Street. Commercial corridors. Not farmland. Not scraps. Prime urban real estate. While others speculated, he owned. By the 1880s, Church was the largest Black landowner in the South. By the 1890s, he was worth over one million dollars—making him the first Black millionaire in the South after slavery, at a time when lynchings were public entertainment and Jim Crow was tightening its grip. But Church didn’t just build wealth for himself. He understood something most wealthy people do: money without community is fragile. He invested heavily in Black Memphis. He built Church Park and Auditorium, one of the largest Black-owned entertainment venues in the country. It hosted concerts, political meetings, conventions, and speeches by leaders like Booker T. Washington. When Black people were locked out of public spaces, Church created their own. He financed Black businesses when banks refused. He backed schools when the state neglected them. He used his influence to protect Black institutions during periods of racial terror—not with speeches, but with ownership and political pressure. And then came 1892. That year, Memphis exploded with racial violence after the lynching of three successful Black businessmen. Many Black residents fled the city, fearing massacre. Again, white landowners sold. Again, Robert Reed Church bought. His wealth grew not from exploitation—but from discipline, timing, and understanding systems. Church also understood legacy. His son, Robert Reed Church Jr., became one of the most powerful Black political figures in America, helping found the NAACP and turning Memphis into a center of Black political organization. This was not accidental. This was design. Robert Reed Church died in 1912, but his blueprint remains painfully relevant today. He proved that Black wealth was never impossible—only interrupted. He proved that land ownership is power. He proved that economic independence is louder than protest. And he proved that when Black people are allowed—even briefly—to operate without sabotage, they build cities. They erased his name because his existence is evidence. Evidence that Black Wall Streets didn’t appear by accident.Evidence that wealth can be built even in hostile systems.Evidence that the problem was never Black ability—but white interference. Robert Reed Church didn’t beg for inclusion. He bought the ground beneath the system—and stood on it. SEO Elements Slug:robert-reed-church-first-black-millionaire-south Meta Description:The untold story of Robert Reed Church, the first Black millionaire in the South after slavery, who built wealth through land ownership, discipline, and economic independence in Memphis.

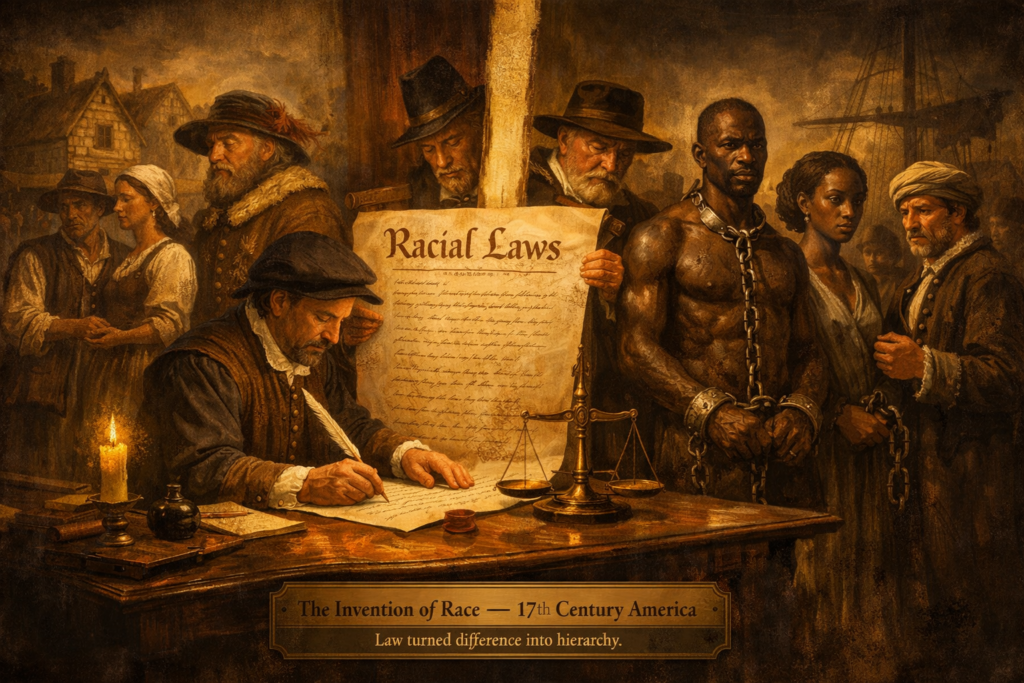

How “White” Was Invented — And How Black People Were Branded in the Process

Before America existed, before plantations, before racial laws, and before the word “white” ever carried meaning, Europe was already brutal—but not divided by skin color. It was divided by power. In medieval Europe, no one woke up calling themselves white. That identity did not exist. A poor English farmer had nothing in common with a wealthy English lord, and no amount of shared skin tone could bridge that gap. Identity came from land, lineage, loyalty, and religion. You were Saxon or Norman, Irish or Frank, Catholic or Protestant, noble or peasant. Those labels determined your fate far more than complexion ever did. Most Europeans lived under a rigid system of hierarchy where kings and nobles owned land and everyone else existed to serve it. Serfs were bound to estates they would never own, working fields they could never profit from, paying taxes they could never escape. Their lives were short, their labor exploited, and their bodies disposable. Poverty was inherited. Wealth was protected. Freedom was rare. A peasant in England was closer in social status to an enslaved laborer than to a noble of his own nation. Religion sharpened these divisions even further. In Europe, belief defined belonging. Christian versus Muslim. Catholic versus Protestant. Christian versus Jewish. During the centuries when Africans and Arabs ruled much of Spain under Al-Andalus, darker-skinned people governed some of the most advanced cities in Europe. Cordoba and Granada had paved streets, libraries, and universities while much of northern Europe remained illiterate and rural. But when Christian kingdoms reclaimed Iberia during the Reconquista, they did more than seize land. They introduced a dangerous idea that would later shape the modern world: purity of blood. Spain’s “limpieza de sangre” system judged people not just by belief, but by ancestry. Converted Christians with African or Jewish lineage were still considered tainted. This was not yet whiteness, but it was the blueprint. Bloodlines were being ranked. Worth was becoming inherited. Humanity was being filtered through ancestry rather than character or faith. At the same time, Europeans themselves were being enslaved. Long before the transatlantic slave trade, bondage in Europe was common. Vikings captured and sold other Europeans across trade routes. Slavic peoples were enslaved so frequently that their name became the root of the word “slave.” Along the North African coast, thousands of Europeans were taken during raids and forced into labor within the Ottoman world. Enslavement was not racial—it was about power. Whoever controlled land, weapons, and law decided who was free. Everything changed when Europe reached the Americas. Colonial elites quickly learned a dangerous lesson: poor Europeans and Africans working together were a threat. Uprisings like Bacon’s Rebellion revealed that class solidarity could destabilize colonial power. The response was not justice, but invention. A new identity was created—one that had never existed before. “White.” Whiteness was not culture. It was not heritage. It was law. Colonial governments passed statutes that granted poor Europeans small privileges—access to land, lighter punishments, legal protections—while Africans were stripped of humanity permanently. Slavery became lifelong. Slavery became inherited. Freedom became tied to skin color. The racial categories of “white” and “black” were born together, serving opposite purposes within the same system. This invention worked exactly as intended. It divided laborers who might have united. It redirected anger away from elites and toward the enslaved. It gave poor Europeans a psychological wage in place of real economic power. They were no longer peasants or servants—they were white. And that label carried just enough status to protect the system that continued to exploit them. This is why understanding history matters. Because race was never about biology. It was about control. Whiteness was created to protect wealth, not people. Blackness was imposed to justify extraction, exploitation, and permanent subjugation. Once you understand this, the modern world begins to make sense—from wealth gaps to policing, from labor inequality to global power structures. The story we were taught was incomplete by design. But when you trace it back far enough, the truth becomes unavoidable. Race didn’t create hierarchy.Hierarchy created race. ❤️ Support Independent Black Media Black Dollar & Culture is 100% reader-powered — no corporate sponsors, just truth, history, and the pursuit of generational wealth. Every article you read helps keep these stories alive — stories they tried to erase and lessons they never wanted us to learn. Hashtags#BlackHistory #HiddenHistory #RaceWasInvented #Whiteness #BlackDollarAndCulture #Colonialism #PowerStructures #EconomicHistory #TruthOverMyths #GlobalHistory Slug:how-whiteness-was-invented-and-how-black-people-were-branded Meta Description:Discover how race was invented to protect power—how Europeans became “white,” how Black people were branded, and how hierarchy shaped the modern world.

Amenhotep III: The African Pharaoh Who Ruled Egypt at Its Absolute Peak

Long before decline, invasion, and distortion crept into the historical record, there was a moment when Egypt stood uncontested—politically, economically, culturally, and spiritually. That moment belonged to Amenhotep III. His reign was not built on constant warfare or desperate expansion, but on something far rarer in the ancient world: total dominance so complete that peace itself became a symbol of power. Under Amenhotep III, Egypt did not merely survive history—it defined it. He ascended the throne in the 14th century BCE, inheriting a kingdom already strong, but what he transformed it into was unprecedented. Egypt became the axis of the known world. Gold flowed through its cities like blood through arteries. Foreign kings did not challenge Egypt—they courted it. They sent tribute, daughters, luxury goods, and diplomatic letters not as equals, but as petitioners seeking favor from the African superpower seated along the Nile. This was not accidental. Amenhotep III ruled during a time when Nubian gold mines were fully operational, giving Egypt control over the most valuable resource of the Bronze Age. Gold was not symbolic—it was structural. It funded architecture on a scale never seen before, paid craftsmen whose skills bordered on divine, and allowed Egypt to project power without raising a sword. Where other empires conquered through fear, Egypt under Amenhotep III conquered through gravity. Everything was pulled toward it. The monuments tell the story even when the texts are ignored. Colossal statues rose from the earth not as propaganda, but as statements of reality. Temples were not hurried structures of defense but carefully planned expressions of eternity. The Colossi of Memnon—towering figures seated in silence—were not meant to intimidate enemies. They were meant to remind the world that Egypt, and its king, were permanent. These were not the works of a kingdom bracing for collapse, but of one utterly confident in its place atop human civilization. Amenhotep III did something few rulers in history ever achieved: he ruled so well that war became unnecessary. His foreign policy was built on diplomacy, marriage alliances, and economic leverage. The Amarna Letters—diplomatic correspondence between Egypt and other great powers—reveal foreign rulers openly begging for gold, addressing the pharaoh as a brother while knowing full well the imbalance between them. Babylon, Mitanni, Assyria—names that loom large in ancient history—all acknowledged Egypt’s supremacy during his reign. Inside Egypt, life reflected that stability. Art flourished, not as rigid symbolism but with softness, realism, and confidence. Faces gained individuality. Bodies showed movement and ease. This was the aesthetic of a society at peace with itself. Religion expanded as well, with Amenhotep III increasingly associated with divine attributes during his lifetime. He was not merely a king chosen by the gods—he was a living manifestation of cosmic order, Ma’at itself embodied in human form. It is no coincidence that his reign is remembered as the golden age. This was the apex—the point at which wealth, culture, spirituality, and global influence aligned perfectly. Everything before led to it. Everything after struggled to live up to it. Even his successors ruled in the long shadow he cast. His son, Akhenaten, would attempt to reshape religion entirely, not from weakness, but from the confidence inherited from a world already conquered by his father. Tutankhamun, whose name eclipsed Amenhotep III in modern popular culture, ruled a diminished echo of that greatness, remembered largely because the artifacts of his burial survived untouched. History, however, has a habit of obscuring African power when it becomes inconvenient. Amenhotep III is often reduced to a prelude, a name mentioned quickly before the so-called “interesting” period begins. But this framing is backwards. There is no later drama without his stability. There is no religious revolution without his wealth. There is no global Egypt without his diplomacy. He is not a footnote—he is the foundation. What makes Amenhotep III truly remarkable is not just what he built, but what he proved. He demonstrated that African civilization could dominate the world without perpetual violence. That wealth could be institutional, not extractive. That culture could be both sacred and luxurious. That leadership rooted in balance, not chaos, could sustain an empire at its absolute height. When Egypt is discussed as a mystery, as a marvel detached from Africa, Amenhotep III stands as a correction. His reign was unmistakably African in origin, power, and identity. The Nile was not a backdrop—it was the engine. The people were not passive laborers—they were participants in a civilization conscious of its greatness. This was not borrowed glory. It was built, refined, and ruled by Africans at the highest level humanity had yet seen. Amenhotep III did not rule during Egypt’s rise, nor its decline. He ruled at the peak—the summit where everything worked. And history has been trying to climb back there ever since. Slug: amenhotep-iii-african-pharaoh-egypt-absolute-peakMeta Description: Amenhotep III was the African pharaoh who ruled Egypt at its absolute peak of wealth, peace, diplomacy, and global power—an unmatched golden age in human history.

Madam C.J. Walker: The First Self-Made Black Woman Millionaire America Tried to Forget

Before Silicon Valley. Before hedge funds. Before Wall Street started pretending it understood “self-made.”There was Madam C. J. Walker—a Black woman born into the ashes of slavery who built an empire so powerful it terrified the systems designed to keep her small. She was not handed opportunity.She was not invited into rooms.She was not protected by laws, banks, or sympathy. She built anyway. Born in 1867, just two years after the end of slavery, Sarah Breedlove entered a country that had legally ended bondage but economically perfected it. Her parents had been enslaved. Her childhood was marked by loss. Orphaned by seven, married by fourteen, widowed by twenty, and raising a daughter alone, she lived the kind of life America usually erases—not because it’s rare, but because it exposes the lie. The lie that success is granted fairly.The lie that hard work is enough—unless you own the system. Sarah worked as a washerwoman, scrubbing clothes for pennies while breathing in steam and chemicals that damaged her scalp so badly her hair began to fall out. But what others saw as humiliation, she treated like research. She listened. She observed. She experimented. And then she made a decision that would echo across generations: She stopped asking for permission. She studied hair care the same way financiers study markets. She learned chemistry, formulation, branding, and sales—without a degree, without capital, without protection. When she created her first successful hair product, she didn’t sell it quietly. She sold it boldly, face-to-face, door-to-door, Black woman to Black woman. She renamed herself Madam C.J. Walker—not to impress white America, but to signal authority to her own people. In an era where Black women were called “girl” well into old age, she crowned herself Madam and dared anyone to object. They didn’t know what to do with her. Walker didn’t just sell products—she built infrastructure. She opened factories. She purchased real estate. She trained thousands of Black women as sales agents, not as servants but as entrepreneurs, teaching them financial literacy, confidence, and independence in a society that wanted them invisible. Her agents—called “Walker Agents”—earned commissions, owned businesses, traveled the country, and sent their children to school. At a time when Black labor was exploited and controlled, she created ownership. And that was the real threat. By the early 1900s, Walker had built a national brand. She employed thousands. She reinvested heavily into Black institutions—schools, churches, newspapers, and civil rights causes. She donated to anti-lynching campaigns when silence was safer. She funded Black education when the state refused to. She understood something America still struggles to admit: Wealth is not about money.It’s about leverage. When she built her mansion, Villa Lewaro, in New York, it wasn’t indulgence—it was strategy. A visible declaration that Black excellence could not be hidden, that success did not need white approval to be legitimate. The backlash was predictable. White media minimized her. Historians downplayed her. The phrase “self-made” was twisted to exclude her, even though she built from literal nothing. For decades, her story was softened, diluted, reduced to “hair care” instead of what it truly was: A masterclass in Black capitalism. Madam C.J. Walker didn’t just get rich—she redistributed power. She created a blueprint modern America still refuses to teach: • Control production• Own distribution• Train your people• Reinvest into the community• Use wealth as a weapon against injustice When she died in 1919, she was one of the wealthiest women in the country—Black or white. But more importantly, she left behind a network of educated, financially independent Black women who knew their value and refused to shrink. That was her real inheritance. Today, her name is finally resurfacing, often stripped of its sharpest edges, packaged as inspiration without instruction. But Madam Walker was not a motivational quote. She was a warning. A warning of what happens when Black people are left alone long enough to build. Her life answers a question America still avoids: What would this country look like if Black builders had never been sabotaged? The answer is uncomfortable.So they buried the evidence. But history has a habit of resurfacing when the moment demands it. And right now—when ownership is once again the dividing line between survival and struggle—Madam C.J. Walker’s story isn’t just history. It’s instruction. ❤️ Support Independent Black Media Black Dollar & Culture is 100% reader-powered — no corporate sponsors, just truth, history, and the pursuit of generational wealth. Every article you read helps keep these stories alive — stories they tried to erase and lessons they never wanted us to learn. Slug:madam-cj-walker-first-self-made-black-woman-millionaire Meta Description:Madam C.J. Walker was the first self-made Black woman millionaire, building a business empire from nothing while empowering thousands of Black women and reshaping American economic history.

The Significance of December 19, 1865: A Pivotal Moment in Black History

Understanding the 13th Amendment The 13th Amendment, ratified on December 6, 1865, represents a critical juncture in American history, particularly in the advancement of civil rights for African Americans. It abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime, thereby laying the groundwork for future legislative and social reforms aimed at achieving equality. The Amendment’s roots can be traced back to the broader context of the Civil War, where the fight against the Confederacy was also a fight against the institution of slavery itself. The passage of the 13th Amendment was championed by numerous abolitionists, politicians, and leaders of the Union. Key figures such as President Abraham Lincoln played a pivotal role, utilizing his influence to promote emancipation as a war measure. During the war, the moral imperative to end slavery gained traction, causing a significant shift in public opinion. This advocacy was set against a backdrop of intense political strife, as various factions within Congress debated the future of the Union and the fate of millions of enslaved individuals. The political climate of the time was marked by a struggle for power between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions. The Republican Party, having emerged from the abolitionist movement, found its platform centered around the idea of freedom for all individuals. The Civil War solidified the urgency for the passage of the 13th Amendment, as the Union victory prompted discussions about the reconstruction of the nation and the status of freed slaves. Ultimately, the amendment’s ratification marked a significant change in the constitutional fabric of the United States, signaling a new era in which African Americans could begin to claim their rights as free citizens. The Implications of Freedom without Economic Power The abolition of slavery in 1865 marked a significant milestone in American history, ushering in a new era of freedom for African Americans. However, this newfound freedom often came with the harsh reality of economic disenfranchisement. While individuals were freed from the shackles of bondage, they were not provided with the resources or opportunities necessary to thrive in a competitive economy. The transition from slavery to freedom did not automatically translate into equality, particularly in terms of economic power. Many newly freed African Americans found themselves without land, capital, or education, which severely limited their ability to achieve financial independence. The promise of land grants and economic support was largely unmet, leaving them to navigate a landscape marred by systemic barriers. The practice of sharecropping emerged as a dubious solution, perpetuating a cycle of debt and poverty. In this system, African Americans would rent land from white landowners in exchange for a share of the crop, often leading to exploitation and barely subsistence living. Moreover, labor exploitation was rampant, as many freed individuals were relegated to low-paying jobs that offered no room for advancement. Economic opportunities were scarce, as racial discrimination restricted access to skilled employment and education. Such circumstances perpetuated economic disparities that would haunt Black communities for generations. Without access to economic resources, the struggle for true freedom continued, affecting the social fabric and future prospects of African Americans. This intersection of freedom with economic power underscores an essential understanding of Black history, highlighting the ongoing challenges faced by these communities in their pursuit of equality. Legacy of the 13th Amendment in Modern America The passage of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865, marked a significant turning point in American history by signaling the formal abolition of slavery. However, the legacy of this pivotal amendment extends far beyond its initial intent, as it continues to influence discussions on racial inequality and social justice in contemporary society. While the formal institution of slavery ended, various systemic issues, such as mass incarceration and economic disparities, have arisen that disproportionately affect African Americans. Mass incarceration has emerged as a leading concern in discussions surrounding the 13th Amendment. Many advocates argue that although the amendment abolished slavery, it inadvertently allowed for a new form of servitude through prison labor. The current penal system, with its disproportionate representation of Black individuals, raises critical questions about the true nature of freedom. Activists cite the over-policing of African American communities and harsh sentencing laws as modern manifestations of racial discrimination that demand attention and reform. In addition to incarceration, economic empowerment remains a significant challenge for African Americans. Despite legal advancements since the 13th Amendment, there are ongoing disparities in wealth and employment opportunities. Efforts to address these disparities, such as advocating for fair hiring practices and equitable access to education, are essential steps towards achieving true equality. Grassroots movements led by organizations focused on civil rights, such as Black Lives Matter, have emerged in response to these challenges, further emphasizing the need for systemic change. In examining the enduring legacy of the 13th Amendment, it is clear that the fight for freedom and equality for African Americans is far from complete. Historical and contemporary issues intersect to create a complex landscape that requires continued advocacy and policy reform to ensure that the promise of the 13th Amendment is fully realized. Only through persistent efforts can the ideals of freedom and equality be truly achieved for all citizens. Commemoration and Reflection on December 19 December 19, 1865, marks a significant turning point in Black history, representing a time when African Americans began to gain momentum in their fight for freedom and equality. This date is not only a historical milestone but also serves as a reminder of the ongoing struggles faced by Black communities. In the years since, various educational initiatives have been instituted to ensure that this pivotal moment is recognized and remembered. Schools, colleges, and community organizations often host events on this day to foster awareness and understanding of its importance. Black leaders and movements play a crucial role in advocating for economic justice, promoting the significance of this date as a cornerstone of freedom. These leaders often remind us that the fight for equality extends beyond the abolition of slavery, encompassing various facets of social justice, including access

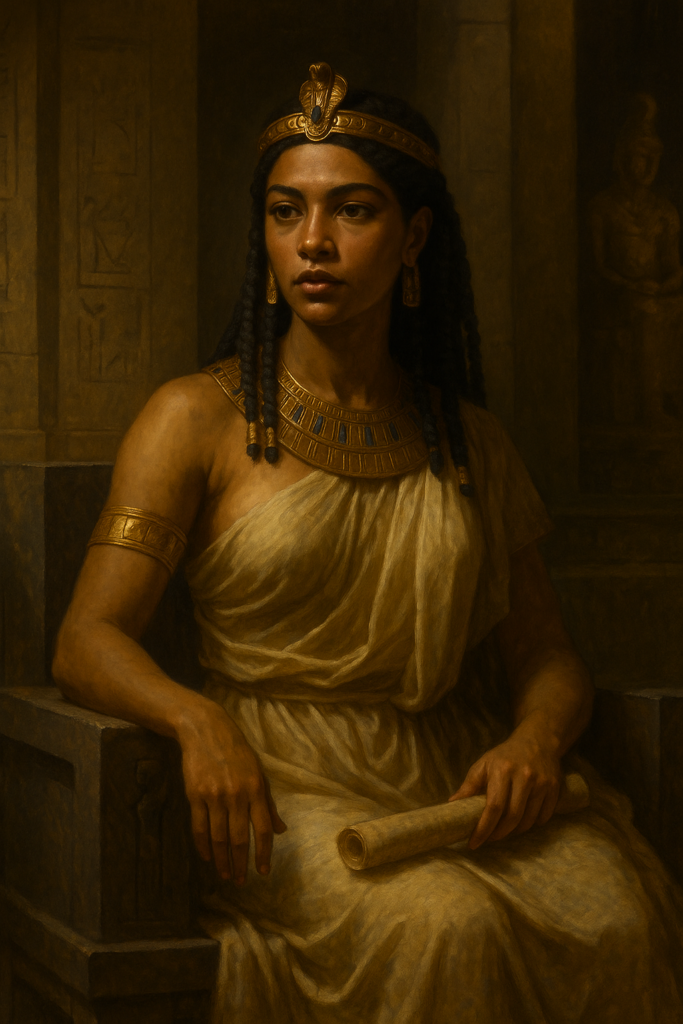

Cleopatra VII: The Wealthiest Queen Rome Ever Feared

History remembers Cleopatra VII as a lover, a seductress, a woman whose power supposedly came from beauty and manipulation. That version of her story is convenient. It’s also a lie. Cleopatra VII was not dangerous because of romance. She was dangerous because she controlled one of the richest economies on Earth at the exact moment Rome was starving for resources, legitimacy, and money. Empires do not smear women they consider harmless. They rewrite the stories of rulers who threaten them. When Cleopatra took the throne of Egypt in 51 BCE, she inherited more than a crown. She inherited an economic machine that had fed civilizations for centuries. Egypt was not simply a kingdom; it was the financial backbone of the Mediterranean world. Its grain fields along the Nile supplied food to Rome’s swelling population. Its ports controlled trade routes between Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Its treasuries held gold, silver, and state reserves accumulated over generations. Cleopatra did not stumble into power. She was trained from childhood to manage it. Unlike many rulers of her era, Cleopatra spoke multiple languages fluently, including Egyptian, Greek, and Latin. This was not a cultural flex; it was a strategic weapon. She could negotiate directly with merchants, diplomats, and military leaders without translators who diluted meaning or leaked information. She understood trade, taxation, logistics, and statecraft. Cleopatra ruled Egypt not as a figurehead but as a chief executive of a sovereign economic power. Rome, by contrast, was drowning in ambition and debt. Its military campaigns were expensive. Its political elite fought constantly for dominance. Its population depended heavily on Egyptian grain to avoid famine and unrest. Cleopatra knew this. She understood leverage better than most men who sat in the Roman Senate. Control the food, and you control the empire that eats it. When Julius Caesar entered her story, it was not romance that drew Cleopatra to him; it was survival and strategy. Egypt faced internal power struggles and Roman interference. Aligning with Caesar stabilized her throne and protected Egypt’s autonomy. In return, Rome gained access to Egypt’s resources under negotiated terms rather than outright conquest. Cleopatra used diplomacy to buy time, preserve sovereignty, and keep Egypt independent in a world where Rome swallowed kingdoms whole. After Caesar’s assassination, Cleopatra aligned with Mark Antony, not as a love-struck queen but as a ruler securing military protection and political balance. Together they controlled enormous territory, trade routes, and naval power. At their height, Cleopatra and Antony governed lands that rivaled Rome’s influence. This was not scandal; it was geopolitics. Rome did not panic because Cleopatra was charming. Rome panicked because she was effective. What followed was not merely a military conflict but a propaganda war. Octavian, later known as Augustus, understood that Rome could not admit it feared a foreign Black queen who commanded wealth, loyalty, and economic leverage. So he reframed the narrative. Cleopatra became painted as immoral, manipulative, and decadent. Antony was portrayed as weak and corrupted by foreign influence. This narrative justified Rome’s aggression and masked the truth: Rome crushed Egypt not to save morality, but to seize resources. After Cleopatra’s death, Egypt was absorbed into the Roman Empire. Its treasuries were looted. Its grain supply was nationalized for Rome’s benefit. The wealth Cleopatra once controlled now fed Roman dominance for generations. And just like that, history shifted its tone. Cleopatra’s intelligence was erased. Her financial mastery was ignored. Her leadership was reduced to gossip. But facts do not disappear simply because empires prefer myths. Cleopatra VII ruled one of the richest states in human history. She controlled food, trade, gold, language, and diplomacy with precision. She understood that power is not loud; it is organized. And that is why Rome destroyed her image after destroying her kingdom. They could defeat her militarily, but they could not allow future generations to understand what she truly represented: a sovereign ruler who proved that wealth, intelligence, and strategy are far more threatening than swords. Cleopatra’s legacy is not romance. It is a lesson. Those who control resources shape the world, and those who challenge empires rarely get fair biographies. History often belongs to the victors, but wealth always leaves a trail. And if you follow the money, the grain, and the power, you find Cleopatra VII exactly where Rome feared her most — at the center of the economic world. ❤️ Support Independent Black Media Black Dollar & Culture is 100% reader-powered — no corporate sponsors, just truth, history, and the pursuit of generational wealth. Every article you read helps keep these stories alive — stories they tried to erase and lessons they never wanted us to learn. Focus Keyphrase: Cleopatra VII wealth and power Slug: cleopatra-vii-wealth-power-rome Meta Description: Cleopatra VII was not just a queen but a powerful economic strategist who controlled Egypt’s wealth, trade, and grain supply—making her one of the most feared rulers Rome ever faced.