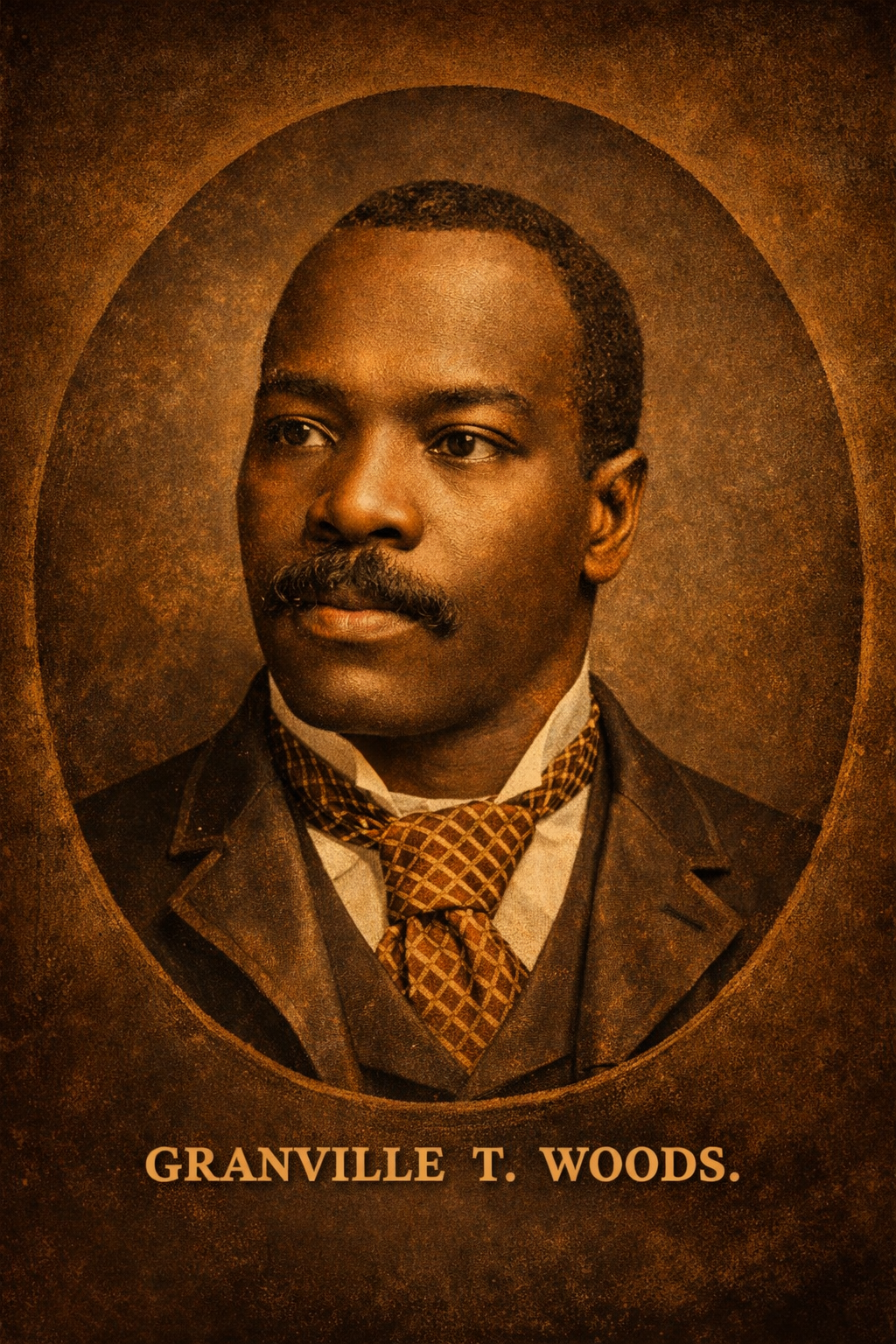

Long before America celebrated innovation as a corporate achievement, before patents became weapons and genius was filtered through race and power, a self-taught Black engineer was quietly reshaping the future of the nation. His name was Granville T. Woods, and the modern world still runs on systems influenced by his mind, even if history has tried to forget him.

Born in 1856 in Columbus, Ohio, just one year after the official end of slavery, Woods entered a country that had little interest in protecting Black intellect. Formal education was limited, but necessity became his classroom. As a teenager, he worked in machine shops, steel mills, and on railroads, absorbing mechanical knowledge firsthand. Where others saw labor, Woods saw systems. Where others followed instructions, he asked why things worked—and how they could work better.

Railroads in the late 19th century were expanding rapidly, but they were also deadly. Trains collided frequently because communication between moving locomotives and stations was unreliable. Signal systems lagged behind the speed of industrial growth, and passengers paid the price. Woods recognized electricity as the missing link. At a time when electrical engineering was still in its infancy, he envisioned wireless communication between trains and control stations—an idea well ahead of its time.

That vision became reality through his invention of the induction telegraph. This system allowed trains to communicate with stations and other trains without physical wires, drastically reducing collisions and improving coordination across rail networks. It was not a minor upgrade; it was a foundational leap in transportation safety. Modern rail signaling, subway communication systems, and even elements of wireless transit technology trace conceptual roots back to Woods’ work.

But invention was only half of Woods’ struggle. Ownership was the other.

In an America where white inventors were celebrated and Black inventors were questioned, Woods was forced into constant legal battles to defend his patents. Powerful industrial figures challenged his claims, attempting to absorb his ideas into their own portfolios. Among them was Thomas Edison, one of the most famous inventors in American history.

Edison disputed several of Woods’ patents, particularly those related to electrical transmission and communication systems. The legal battles were not symbolic—they were brutal, expensive, and exhausting. Yet Woods won. Multiple courts ruled in his favor, affirming that his ideas were original and his claims legitimate. These victories were rare for a Black inventor in that era and underscored the undeniable brilliance of his work.

Ironically, after losing to Woods in court, Edison offered him a position at Edison Electric Light Company. Woods declined. He understood that employment would mean surrendering independence and potentially losing control of future inventions. Instead, he chose the harder path: remaining an independent inventor in a system stacked against him.

Woods’ contributions extended far beyond railroads. He held more than 60 patents, many focused on electrical systems, power distribution, and transportation. His work improved electric streetcars, helped develop overhead power lines, and advanced the efficiency of electrical transmission in growing cities. Urban America—its subways, trolleys, and commuter systems—benefited enormously from his innovations.

Yet unlike his white contemporaries, Woods did not amass wealth. Patent litigation drained his resources. Corporations profited from his ideas while he struggled to maintain financial stability. By the time of his death in 1910, he was respected among engineers but virtually invisible to the public. No fortune. No national recognition. No textbooks honoring his name.

This pattern was not accidental. It reflected a broader American reality: Black innovation was essential, but Black ownership was optional. Woods’ story mirrors countless others where genius was extracted, repackaged, and monetized by institutions that refused to credit its true source. His life exposes the uncomfortable truth that America’s technological rise was fueled not just by celebrated inventors, but by marginalized minds denied their rightful place in history.

Today, as conversations around equity, ownership, and intellectual property resurface, Granville T. Woods’ story feels painfully modern. He was not merely a victim of his time; he was a warning. Innovation without protection leads to exploitation. Genius without ownership leads to erasure.

Restoring Woods to his rightful place is not about nostalgia. It is about understanding the foundation of modern America. The trains that move millions each day, the communication systems that ensure their safety, and the electrical infrastructure that powers cities all carry echoes of his work. His fingerprints are everywhere, even when his name is not.

Granville T. Woods was more than an inventor. He was proof that Black intellect has always been central to progress—even when history refused to acknowledge it. Remembering him is not rewriting history. It is finally telling it honestly.

Focus Keyphrase: Granville T. Woods Black Inventor

Slug: granville-t-woods-black-inventor

Meta Description: Granville T. Woods was a brilliant Black inventor whose electrical innovations transformed railroads and powered modern America, including winning patent cases against Thomas Edison.