Elijah McCoy: The Black Inventor Whose Genius Became the Standard for the World

Elijah McCoy was born into a nation that benefited from Black intelligence while refusing to honor it. The son of formerly enslaved parents, McCoy entered a world where freedom existed on paper, but opportunity did not. Yet even inside that reality, his mind operated on a level so advanced that the industrial world was forced to adapt to him—even while trying to erase his name. From an early age, McCoy displayed a rare mechanical brilliance. His parents, recognizing what they had, made an extraordinary sacrifice and sent him to Scotland to study mechanical engineering. At a time when most Black Americans were barred from formal education, McCoy became fully trained in the science of machinery, precision systems, and industrial mechanics. He returned to the United States prepared to work as an engineer—but America refused to let him be one. Instead, McCoy was hired as a railroad fireman and oiler, jobs far beneath his qualifications. But what appeared to be a demotion became an advantage. Inside the belly of the industrial machine, McCoy observed a problem no one else was equipped to solve. Steam engines powered the economy, but they were inefficient. They had to be stopped repeatedly so workers could manually lubricate moving parts. Every stop meant lost time, wasted money, and reduced productivity. McCoy saw the flaw clearly—and he fixed it. He designed an automatic lubrication system that allowed engines to oil themselves while running. Machines no longer needed to shut down. Railroads ran longer. Factories became more efficient. Heavy machinery gained endurance and reliability. His invention quietly transformed industry, setting a new standard for how machines should operate. The impact was immediate and undeniable. McCoy’s lubrication systems were so effective that inferior copies flooded the market. But engineers and buyers quickly learned the difference. They refused substitutes. When ordering equipment, they demanded only the authentic design. They wanted the real McCoy. That phrase—now used worldwide to describe authenticity and excellence—was born directly from the work of a Black inventor whose name history often omits when repeating it. Over his lifetime, Elijah McCoy secured more than 50 patents, many centered on lubrication systems, mechanical efficiency, and industrial improvement. Yet like so many Black innovators, he struggled to benefit financially from his own brilliance. Racism blocked access to investors, manufacturers, and ownership opportunities. Corporations and industries thrived using systems inspired by his ideas, while McCoy himself lived without the wealth his inventions generated. Still, his legacy could not be denied. Every modern engine designed for continuous operation carries his influence. Every industrial system built to reduce friction, prevent failure, and maximize efficiency reflects his thinking. McCoy did not simply invent devices—he defined reliability itself. His life exposes a larger truth: Black inventors were not behind progress. They were ahead of it. They built the backbone of modern industry while being denied credit, capital, and protection. Elijah McCoy’s genius was so undeniable that the world immortalized his name as a guarantee of quality—even while refusing to properly honor the man behind it. Elijah McCoy is not a footnote. He is a foundation. And understanding his story is not just about the past. It is about reclaiming the truth of who built the systems that still power the world today. 🔑 Focus Keyphrase Elijah McCoy Black Inventor 🔗 Slug elijah-mccoy-black-inventor-real-mccoy 🧾 Meta Description Elijah McCoy was a revolutionary Black inventor whose engineering genius transformed the Industrial Age and inspired the phrase “the real McCoy,” now a global symbol of authenticity and excellence.

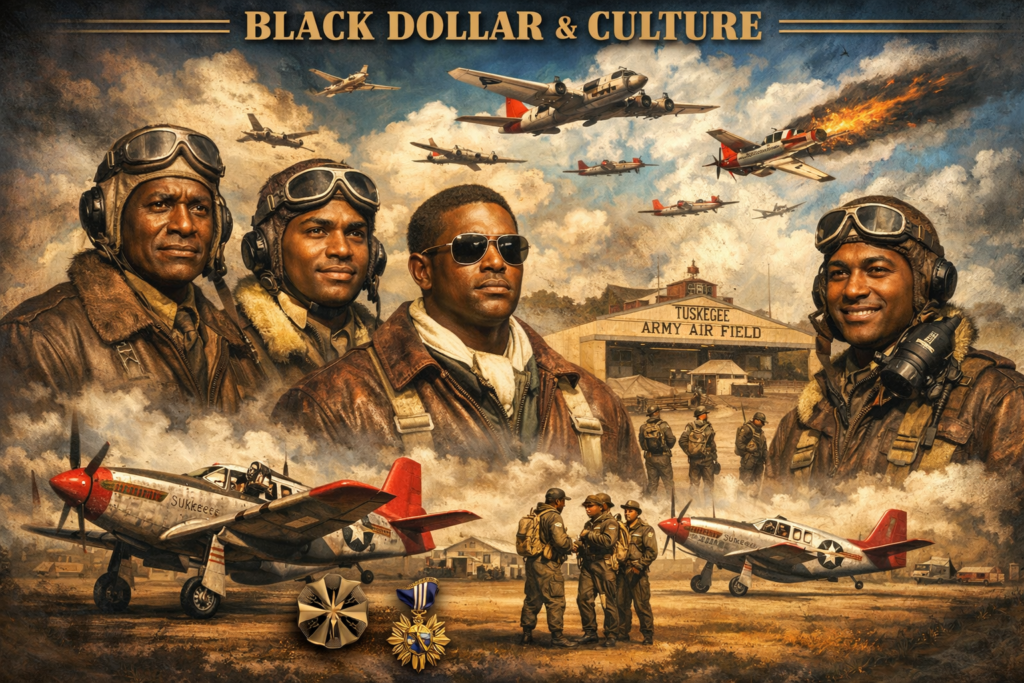

Tuskegee Airmen Black History: The Elite Pilots Who Forced America to End Military Segregation

January 12, 1942 did not arrive with parades, speeches, or national celebration, but history often moves quietly before it roars. On this winter day, in a nation still shackled by segregation and racial mythology, the United States Army Air Forces authorized a program that would challenge one of America’s most deeply held lies: the belief that Black men lacked the intelligence, discipline, and courage to fly military aircraft. From this authorization emerged the men later known as the Tuskegee Airmen—a group whose excellence in the skies would force the nation to confront its contradictions. ❤️ Support Independent Black Media Black Dollar & Culture is 100% reader-powered — no corporate sponsors, just truth, history, and the pursuit of generational wealth. Every article you read helps keep these stories alive — stories they tried to erase and lessons they never wanted us to learn. The establishment of the Tuskegee program did not come from sudden enlightenment. It was the result of pressure, protest, and necessity. Black leaders, civil rights organizations, and newspapers had long challenged the military’s refusal to allow Black pilots, pointing out the hypocrisy of fighting for democracy abroad while denying it at home. World War II, with its demand for manpower, created a crack in the wall. The government conceded, but only partially, and under tightly controlled conditions designed less to empower Black airmen than to test them under a microscope. Training took place at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama, a segregated base in a segregated state. The pilots were trained separately from white counterparts, often with inferior resources, outdated equipment, and instructors who expected failure. Every mistake by a Black cadet was magnified, recorded, and used as supposed proof of racial inferiority. No white unit trained under such pressure. These men were not simply learning to fly; they were fighting an unspoken trial in which the future of Black military aviation hung on every maneuver. Despite these conditions, the men excelled. They mastered navigation, aerial combat, engineering, and leadership. Many already held college degrees at a time when higher education was still largely denied to Black Americans. Their discipline was not accidental—it was forged from the understanding that mediocrity would not be tolerated. Excellence was the minimum requirement for survival, dignity, and progress. When the Tuskegee Airmen were finally deployed overseas, they were assigned to escort Allied bombers deep into enemy territory. This was among the most dangerous missions of the war. Bomber crews depended on fighter escorts to protect them from German aircraft; failure meant death. The Tuskegee Airmen, later known as the “Red Tails” for the distinctive markings on their planes, built a reputation for precision and loyalty. They stayed with the bombers. They did not abandon their posts for personal glory. As a result, they achieved one of the lowest bomber-loss rates of any fighter group in the war. This success directly contradicted decades of pseudoscience and propaganda used to justify segregation. The myth that Black men lacked the mental acuity for complex machinery collapsed under the weight of facts written in combat reports and survival statistics. The myth that Black men lacked courage evaporated in the skies over Europe. What remained was an uncomfortable truth: the barrier had never been ability—it had been racism. Yet recognition did not come easily. While white pilots were celebrated in newsreels and headlines, the Tuskegee Airmen returned home to a country still governed by Jim Crow. They could defeat fascism abroad but not segregation at home. Many were denied jobs in commercial aviation. Some were refused service in restaurants while still wearing their uniforms. The nation had used their skill but hesitated to honor their humanity. Still, history has a long memory, even when institutions try to forget. The success of the Tuskegee Airmen became impossible to ignore. Their record played a crucial role in the 1948 decision by President Harry S. Truman to desegregate the U.S. military, a move that reshaped American armed forces and set a precedent for broader civil rights reforms. Though Truman signed the order, it was the Airmen who earned it with their lives and discipline. The legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen is not confined to military history. It is a lesson in how systems preserve themselves through lies, and how those lies collapse when confronted by undeniable excellence. It is also a reminder that progress in America has rarely been gifted; it has been extracted through pressure, performance, and sacrifice. These men did not simply ask to be included—they proved that exclusion was irrational. Today, when their story is told accurately, it reframes how we understand Black history. It challenges narratives that portray Black advancement as sudden or accidental. The Tuskegee Airmen were scholars, engineers, tacticians, and leaders operating under extreme constraints. Their success was not a fluke; it was the continuation of a long tradition of Black mastery systematically obscured from public memory. January 12 should be remembered not merely as a date, but as a turning point where the lie began to crack. On that day, the United States unknowingly authorized the dismantling of one of its own racist doctrines. The men who trained at Tuskegee did more than learn to fly. They redefined what the nation could no longer deny. They turned the sky into a courtroom, and every successful mission became a verdict. Their story is not just about airplanes or war. It is about truth. And once truth takes flight, it is very hard to bring back down. Focus Keyphrase: Tuskegee Airmen Black HistoryMeta Description: Explore the true story of the Tuskegee Airmen, the Black pilots who shattered racist myths during World War II and reshaped American military history.Slug: tuskegee-airmen-black-history

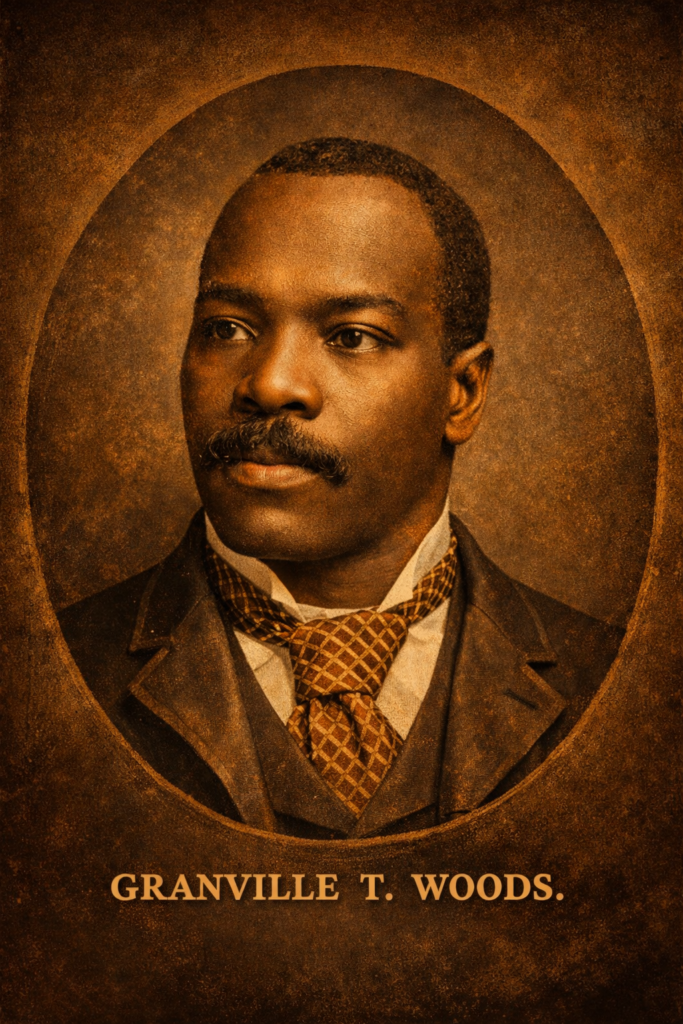

Granville T. Woods: The Black Inventor Who Electrified Modern America

Long before America celebrated innovation as a corporate achievement, before patents became weapons and genius was filtered through race and power, a self-taught Black engineer was quietly reshaping the future of the nation. His name was Granville T. Woods, and the modern world still runs on systems influenced by his mind, even if history has tried to forget him. Born in 1856 in Columbus, Ohio, just one year after the official end of slavery, Woods entered a country that had little interest in protecting Black intellect. Formal education was limited, but necessity became his classroom. As a teenager, he worked in machine shops, steel mills, and on railroads, absorbing mechanical knowledge firsthand. Where others saw labor, Woods saw systems. Where others followed instructions, he asked why things worked—and how they could work better. Railroads in the late 19th century were expanding rapidly, but they were also deadly. Trains collided frequently because communication between moving locomotives and stations was unreliable. Signal systems lagged behind the speed of industrial growth, and passengers paid the price. Woods recognized electricity as the missing link. At a time when electrical engineering was still in its infancy, he envisioned wireless communication between trains and control stations—an idea well ahead of its time. That vision became reality through his invention of the induction telegraph. This system allowed trains to communicate with stations and other trains without physical wires, drastically reducing collisions and improving coordination across rail networks. It was not a minor upgrade; it was a foundational leap in transportation safety. Modern rail signaling, subway communication systems, and even elements of wireless transit technology trace conceptual roots back to Woods’ work. But invention was only half of Woods’ struggle. Ownership was the other. In an America where white inventors were celebrated and Black inventors were questioned, Woods was forced into constant legal battles to defend his patents. Powerful industrial figures challenged his claims, attempting to absorb his ideas into their own portfolios. Among them was Thomas Edison, one of the most famous inventors in American history. Edison disputed several of Woods’ patents, particularly those related to electrical transmission and communication systems. The legal battles were not symbolic—they were brutal, expensive, and exhausting. Yet Woods won. Multiple courts ruled in his favor, affirming that his ideas were original and his claims legitimate. These victories were rare for a Black inventor in that era and underscored the undeniable brilliance of his work. Ironically, after losing to Woods in court, Edison offered him a position at Edison Electric Light Company. Woods declined. He understood that employment would mean surrendering independence and potentially losing control of future inventions. Instead, he chose the harder path: remaining an independent inventor in a system stacked against him. Woods’ contributions extended far beyond railroads. He held more than 60 patents, many focused on electrical systems, power distribution, and transportation. His work improved electric streetcars, helped develop overhead power lines, and advanced the efficiency of electrical transmission in growing cities. Urban America—its subways, trolleys, and commuter systems—benefited enormously from his innovations. Yet unlike his white contemporaries, Woods did not amass wealth. Patent litigation drained his resources. Corporations profited from his ideas while he struggled to maintain financial stability. By the time of his death in 1910, he was respected among engineers but virtually invisible to the public. No fortune. No national recognition. No textbooks honoring his name. This pattern was not accidental. It reflected a broader American reality: Black innovation was essential, but Black ownership was optional. Woods’ story mirrors countless others where genius was extracted, repackaged, and monetized by institutions that refused to credit its true source. His life exposes the uncomfortable truth that America’s technological rise was fueled not just by celebrated inventors, but by marginalized minds denied their rightful place in history. Today, as conversations around equity, ownership, and intellectual property resurface, Granville T. Woods’ story feels painfully modern. He was not merely a victim of his time; he was a warning. Innovation without protection leads to exploitation. Genius without ownership leads to erasure. Restoring Woods to his rightful place is not about nostalgia. It is about understanding the foundation of modern America. The trains that move millions each day, the communication systems that ensure their safety, and the electrical infrastructure that powers cities all carry echoes of his work. His fingerprints are everywhere, even when his name is not. Granville T. Woods was more than an inventor. He was proof that Black intellect has always been central to progress—even when history refused to acknowledge it. Remembering him is not rewriting history. It is finally telling it honestly. Focus Keyphrase: Granville T. Woods Black InventorSlug: granville-t-woods-black-inventorMeta Description: Granville T. Woods was a brilliant Black inventor whose electrical innovations transformed railroads and powered modern America, including winning patent cases against Thomas Edison.

Bessie Coleman: The Woman Who Refused to Stay Grounded

Bessie Coleman was born on January 26, 1892, in Atlanta, Texas, at the intersection of poverty, racism, and rigid limitation. She was the tenth of thirteen children born to George and Susan Coleman, a family of sharecroppers whose lives were shaped by the unforgiving realities of post-Reconstruction America. Cotton fields, long days, and scarce opportunity defined her early years. Education existed, but barely—one-room schoolhouses, worn textbooks, and interrupted learning whenever farm labor demanded it. Yet even in those conditions, Bessie showed an early hunger for knowledge, discipline, and something beyond the horizon. Her father eventually left the family, returning to Indian Territory in Oklahoma in search of a better life, while Bessie remained with her mother, helping raise her siblings and working the fields. Poverty was not an abstract concept to her; it was lived daily. But so was resilience. She excelled in school when she could attend, eventually saving enough money to enroll at Langston University in Oklahoma. Her time there was short—financial hardship forced her to withdraw—but the seed of ambition had already taken root. She would not accept a life dictated by circumstance. In her early twenties, Bessie moved to Chicago, joining the Great Migration of Black Americans seeking opportunity beyond the South. There, she worked as a manicurist, a job that placed her in close proximity to conversation, news, and stories from beyond her world. It was in a barbershop that her life took its decisive turn. She listened as Black men returned from World War I spoke of flying in Europe. They talked about airplanes, freedom, and skies that did not feel segregated. Her brothers, particularly one who had served in France, taunted her—telling her that French women could fly planes while American Black women could not. Instead of discouraging her, the insult ignited something irreversible. Bessie Coleman decided she would fly. The problem was America had no intention of letting her do so. Every aviation school she applied to rejected her. The rejections were absolute—no appeals, no alternatives. She was dismissed not for lack of intelligence or ability, but because she was both Black and a woman. In the early 20th century, flight was considered the domain of white men only. Rather than accept the denial, Bessie made a decision that defined her legacy: if America would not teach her, she would leave America. She enrolled in French language classes, saved her earnings meticulously, and gained sponsorship from influential Black newspapers, including the Chicago Defender. In 1920, she sailed to France. This alone was radical—an unmarried Black woman traveling abroad for professional training at a time when many Americans never left their home counties. In France, she trained at the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation, one of the most respected flight schools in the world. Flying in the 1920s was not glamorous. Planes were unstable, cockpits open to the elements, and crashes common. Training involved risk at every step. Bessie endured crashes, injuries, and intense discipline. But she persisted. On June 15, 1921, she earned her international pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, becoming the first Black woman in the world to do so—and one of the first Americans of any race to hold that distinction. When Bessie returned to the United States, her achievement should have made her a national hero. Instead, she encountered the same walls she had left behind. Airlines would not hire her. Commercial aviation opportunities were closed. Once again, racism tried to ground her ambitions. This time, she refused to stop moving forward. Bessie turned to barnstorming—performing aerial stunts at airshows across the country. Loop-the-loops, dives, figure-eights—she mastered them all. But her performances were not about spectacle alone. They were statements. Every time she climbed into a cockpit, she challenged the idea that Black people belonged only on the ground. She attracted massive crowds, especially in Black communities, where many had never seen an airplane up close, let alone one piloted by a Black woman. She was also uncompromising in her principles. Bessie refused to perform at venues that enforced segregated seating. If Black spectators were forced to enter through back gates or sit separately, she would not fly. This stance cost her income and opportunities, but she would not trade dignity for exposure. To her, flight symbolized freedom, and freedom could not exist alongside humiliation. Her vision extended far beyond stunt flying. Bessie dreamed of opening a flight school for Black aviators—men and women—so future generations would not have to leave the country to learn what she had fought to access. She spoke publicly about this goal, emphasizing education, discipline, and ownership of the skies. She wanted Black pilots, Black mechanics, Black instructors—an aviation ecosystem independent of exclusionary systems. Tragically, that dream was cut short. On April 30, 1926, in Jacksonville, Florida, Bessie Coleman boarded a plane for a practice flight ahead of an upcoming airshow. The aircraft was piloted by her mechanic, William Wills. Bessie was not wearing a seatbelt because she was scouting the terrain below, preparing for a parachute jump she planned to perform later. Mid-flight, the plane experienced a mechanical failure—later determined to be caused by a loose wrench lodged in the engine. The aircraft went into a sudden nosedive. Bessie was thrown from the plane at 2,000 feet and died instantly. She was 34 years old. Moments later, the plane crashed, killing Wills as well. Her death sent shockwaves through Black communities across the country. Thousands attended her funeral in Chicago. Leaders, activists, and ordinary people mourned not just the loss of a woman, but the loss of a future she represented. She died without ever opening the flight school she envisioned, without seeing the aviation doors she cracked open fully swing wide. Yet her impact did not end with her life. Bessie Coleman became a symbol—of courage without permission, of ambition without apology. Her legacy inspired future generations of Black aviators, including the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II. Pilots flew in her honor. Schools, clubs, and scholarships were named

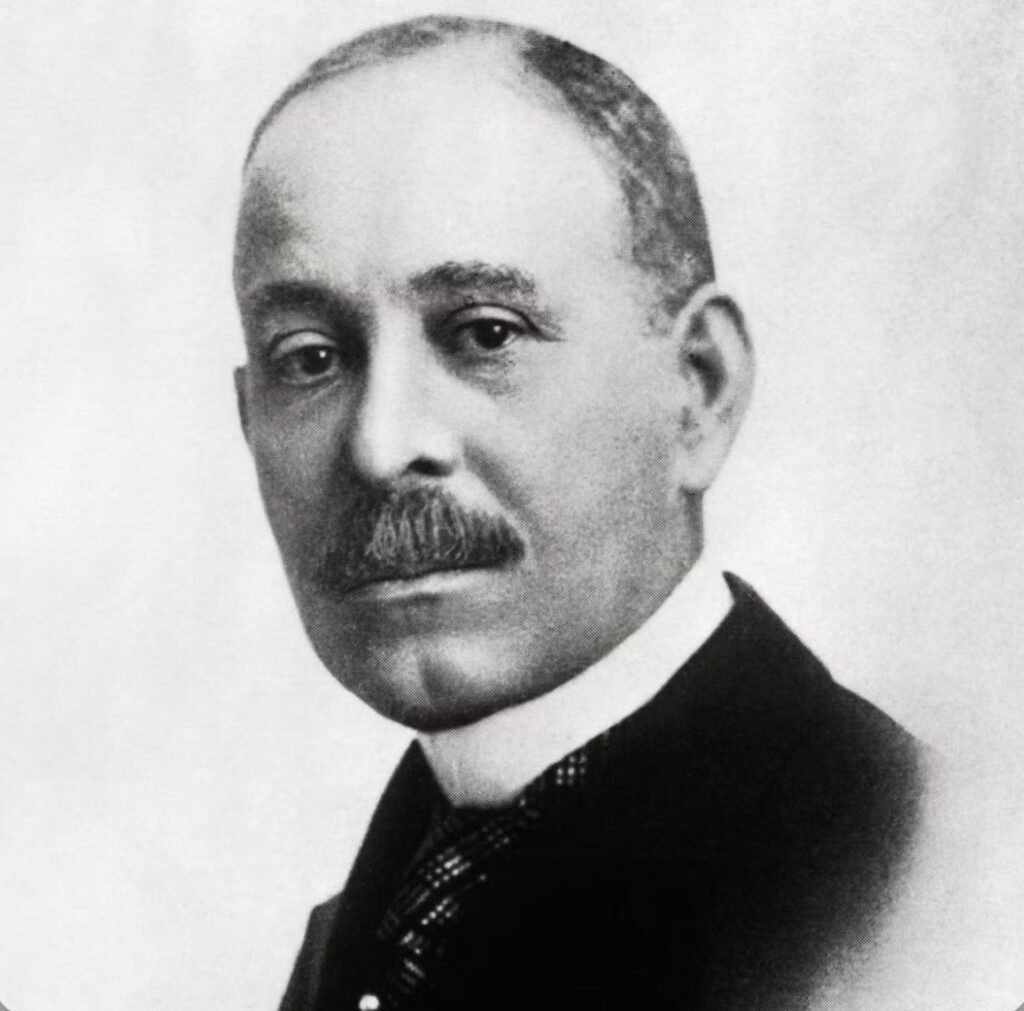

Daniel Hale Williams — The Black Surgeon Who Performed the First Successful Open-Heart Surgery

Before textbooks whispered his name, a Black surgeon in Chicago changed medical history. Daniel Hale Williams opened a man’s chest and repaired a beating heart — at a time when white hospitals refused to treat Black patients. ❤️ Support Independent Black MediaBlack Dollar & Culture is 100% reader-powered — no corporate sponsors, just truth, history, and the pursuit of generational wealth.Every article you read helps keep these stories alive — stories they tried to erase and lessons they never wanted us to learn. 1. The Night That Changed Medicine Forever On July 10, 1893, a man named James Cornish was rushed into Provident Hospital after being stabbed in the chest.His chances of surviving were slim. The heart was considered untouchable — too dangerous to operate on. But Dr. Daniel Hale Williams refused to accept that. At a time when: Williams opened the chest, carefully exposed the heart, and repaired the torn pericardium, the sac that protects it. Cornish lived. Medicine would never be the same. 2. Provident Hospital — When We Build Our Own, We Save Our Own Dr. Williams performed the groundbreaking surgery at Provident Hospital, the first Black-owned, Black-operated hospital in the United States. Why did it exist? Because Black doctors, nurses, and patients were denied treatment in white hospitals. Provident became: Without Provident Hospital, that surgery may never have happened. Ownership wasn’t just economic.It was life and death. 3. Why Most Textbooks Skip This Story Even after proving his brilliance, Dr. Williams faced resistance: Yet his impact is unmistakable: 🏥 Inspired the founding of Black medical institutions🩺 Advanced sterile surgical practices❤️ Proved that heart surgery was possible📚 Opened doors for Black physicians nationwide History didn’t forget him by accident — it was suppressed. 4. Legacy in Modern Medicine Thousands of heart surgeries performed today connect back to that night in 1893. Dr. Williams later helped lead: His legacy lives on every time a heart patient survives what was once a guaranteed death sentence. 5. What This Means for Black America Today This isn’t just history. It’s a blueprint. Lessons we carry forward: ✔ We must own institutions — hospitals, banks, schools, media✔ Black brilliance thrives when barriers are removed✔ Our children must learn not just the history of oppression, but the history of innovation Dr. Williams didn’t wait for permission.He built what we needed. So must we. 📌 Final Word Dr. Daniel Hale Williams didn’t just save a life.He changed the future of medicine — and proved that Black excellence is not new, it is continuous. They tried to shut us out of hospitals, so we built our own.They said heart surgery was impossible — we proved it wasn’t. Our legacy is not struggle.Our legacy is genius. #DanielHaleWilliams #BlackHistory #BlackExcellence #ProvidentHospital #BlackDollarAndCulture #MedicalHistory

The Real Woman Behind Aunt Jemima

Word Count: ~1,250 You’ve seen her face on syrup bottles and pancake mix boxes for decades.That warm smile. That headscarf. That image that became one of the most recognizable brands in American history. But behind the logo was a real woman — a pioneer, a cook, and a performer who was far more than a marketing character. Her name was Nancy Green, and her story is one of brilliance, exploitation, and the power of legacy. 1. From Slavery to Symbol Nancy Green was born into slavery in Montgomery County, Kentucky, in 1834.She lived through an era that denied her humanity — yet she became one of the most influential figures in American consumer history. After gaining her freedom, Nancy moved to Chicago, where she worked as a cook and caretaker. Her skills in the kitchen weren’t just good — they were legendary. So legendary, in fact, that in 1893, she was chosen to represent the Aunt Jemima brand at the World’s Fair in Chicago. That moment changed everything. 2. The Birth of an Icon The Aunt Jemima character was created by two white men — Charles Rutt and Charles Underwood — who based the brand on a minstrel song that mocked Black women. But Nancy Green brought the character to life in a way they never expected. At the World’s Fair, she drew huge crowds. Her pancakes were famous. Her personality was electric. Her storytelling captivated audiences. She turned a caricature into a character — real, relatable, and full of joy. People didn’t just love the pancakes. They loved her. 3. The Face of a National Brand — Without the Fortune Nancy Green became the first living trademark in American advertising history.Her face and likeness sold millions of products. But while her image built wealth for others, she never shared in that success. Quaker Oats bought the Aunt Jemima brand in 1925 and kept her image on the packaging for nearly a century — without ever properly crediting or compensating her descendants. It’s a painful reminder of how Black labor, talent, and creativity built industries that often excluded the very people who made them thrive. Her face made millions. But her legacy was hidden in the fine print. 4. Beyond the Brand — The Real Nancy Green Nancy Green wasn’t just a “mammy” stereotype.She was a philanthropist, a missionary, and a woman of deep faith. She used her platform to support her church and local causes in Chicago.She was known for feeding the hungry, caring for children, and serving her community with the same warmth that made her famous. When she passed away in 1923, she was buried in an unmarked grave — her contributions to history left untold for nearly a century. 5. The Rebrand That Sparked Reflection In 2020, following nationwide conversations about racial imagery and justice, Quaker Oats retired the Aunt Jemima brand. They replaced it with Pearl Milling Company, the original name of the mill that created the pancake mix in 1888. While the move was symbolic, it sparked something more powerful: a reckoning. People began asking, “Who was the real woman behind Aunt Jemima?”And that question led millions to Nancy Green — her story, her strength, and her silence. 6. The Lesson: Own Your Image, Own Your Power Nancy’s story isn’t just history — it’s a blueprint. It reminds us that ownership matters.That every face, every brand, every idea has value. And that when we build — whether it’s a blog, a product, or a brand — we must protect it, name it, and profit from it. The same way they trademarked her image, we must trademark our legacy. Because if you don’t own your image, someone else will — and they’ll sell it back to you. 7. Reclaiming the Narrative Today, Nancy Green’s story is finally being told by educators, historians, and creators like you — people dedicated to rewriting what was erased. Her legacy is more than a syrup bottle. It’s a lesson in self-worth, ownership, and resilience. She was more than Aunt Jemima.She was the blueprint for turning struggle into story — and story into power. Final Word: From Pancakes to Power Nancy Green’s name deserves to be remembered — not as a logo, but as a legacy. She showed the world that even when the odds are stacked, your gift can make the world stop and watch.But her story also warns us — that brilliance without ownership can become bondage all over again. So today, when you see that smiling face on a vintage box, remember the woman behind it.A woman who cooked her way into history.A woman who made a brand unforgettable — even when the world tried to forget her. #NancyGreen #AuntJemima #BlackHistory #BlackExcellence #BlackDollarAndCulture